Learning Outcomes:

- LO2: Demonstrate that challenges have been undertaken, developing new skills in the process

- LO5: Demonstrate the skills and recognise the benefits of working collaboratively

Learning Outcomes:

Learning Outcome:

Learning Outcomes:

Learning Outcome:

I didn’t participate in the preseason this year, so going into the in-season of touch was a bit of a challenge adjusting to the pace of the games and frequency of the trainings. Nearing the end of season 2, we were fortunate to be able to schedule in games with SAS, Tanglin Trust, and Dover. However, we had to abide by the Covid rules and so we played 4v4 games (with 1 sub) on a slightly smaller pitch.

For each of these games, our coach changed up the teams to give the younger girls some exposure to playing with more experienced girls. Initially, it was frustrating not being able to play with my friends or people I was comfortable with, but I think I soon took it as a challenge to work with new girls and see how we could benefit from each other. I think as one of the seniors on the team, we’re often ‘supposed’ to take charge and initiate the strategies and plays on the field. But I think what I gained a lot from these games and this season, in general, was observing how some of these younger girls played and talking with them to discuss what unique things they knew or were comfortable with.

These past few years in touch we’ve taken a different approach to other schools and not selected teams. This has given us the opportunity to train with everyone – regardless of age or ability. I find that a lot of people are sceptical about this and complain it takes a longer time to organise drills during training – but I think it certainly lets us get to know more players and their strengths. A lot of the players are on outside teams or clubs and bring a fresh perspective to game strategies. My goal, as someone who perhaps doesn’t have comparably as much knowledge about the sport, was to initiate conversation and discussion on and off the pitch about what each of the players could offer or share, or raise questions and clarify anything if they were unsure.

We are continuing training as there have been some plans around the organisation of SEASAC among Singapore schools. I aim to use these last few weeks to try to work with some girls I don’t know well and continue to initiate these conversations.

Learning outcome:

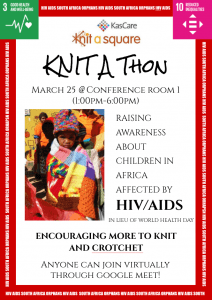

At the start of this year, I decided to take on a personal challenge and audition to be part of the student-led dance production, Culturama. I signed up with my friends for the Tanzanian dance.

This experience has taught me how dance can be used as a tool and platform for cultural expression. I think cultural appreciation has become a sensitive topic, as people are often unsure how to do it in a respectful way or unsure about how to approach a culture outside their own. Since both our dance leaders were not from Tanzania or had any background or prior knowledge about Tanzanian culture, they were required to undergo lots of research and interviews to ensure their dance accurately represented Tanzanian culture.

I, myself do not have a background in Tanzanian dance and so I found that it took me a while to fully grasp the movements and timing with the music. I don’t have a dance background at all and typically find myself more inclined towards the visual arts, so it was a unique experience exploring how a different area of arts is used in another culture. I found it to be a combination of almost all the arts – incorporating elements from drama and music too.

I think watching the Culturama production and the different dances gave me further insight into the types of dance genres around the world and how different and similar they were to one another. Since all of the dances were student-led, it was also interesting to learn about the different artistic choices they made and what they represented. For our dance, our dance leaders wanted to frame the dance around community, togetherness, and celebration in Tanzanian culture – and how that was transposed to our UWC community. As such, we had lots of upbeat movements and joyful music.

Altogether, this experience was incredibly unique and I enjoyed the whole artistic process of rehearsal, trial and error, and getting to perform and share our learning. It would have been nice to be able to compare my experience of being in a Tanzanian dance to one from another country with other students.

Interview with Director of Educational Psychology Ms Low of SHINE Children and Youth Services on 10 May 2021

I was also given the opportunity to meet with the director of educational psychology of an NGO called SHINE that, similar to inlingua, also aims to support the educational sector by providing language and literary support. As an NGO, their primary focus is kids from vulnerable backgrounds – either with social behavioural issues or minimal family support (low income, less supervision, unqualified, lacking support). A large component of what they do is offer diagnosis to manage expectations and support the children, as Ms Low noted a lack of diagnosis or misdiagnosis often leads to much larger social issues in mainstream schools and difficulty to access funding.

The significance of language and literary skills is that learning and social development is very much interrelated. These skills affect their integration into the wider society and their personal well-being. Prior to 1973, the MOE offered little services and school-based support for those with special needs. SHINE’s ‘ground up’ and not ‘top-down’ approach by partnering with other NGOs, schools, hospitals, and working closely with the parents of the students make it easier to offer the appropriate support that fits each student’s needs.

Ms Low also mentioned the importance of a change in attitudes and mindsets from the community. Parents play a huge influence and most commonly perpetuate a competitive study culture and traditional mindset toward disability. Ms Low emphasized the importance of reframing perspectives – focusing on strengths and needs rather than weaknesses/what their child is diagnosed with. There are many uphill struggles with parents coming to terms with their kids’ progress, and this affects how they can offer their child support and how they envision their child contributing to society in a dignified manner.

SHINE works to support the government through various policies, such as campaigns to promote language competencies and accurate communication. They engage with the National Council of Social Service and other SSAs through annual conferences to discuss key thrusts and desired outcomes. As with any organisation, funding and support from volunteers are vital to ensuring they can run their programs. While this may affect the efficiency and quality of their programs, they are able to cater to the most vulnerable of society.

Conducting this interview has allowed me to understand what SHINE does and the programs they run. This also allows me to see the effects and roles of NGOs compared to private institutions (like inlingua) when it comes to supporting government policies and the educational sector.

Pre-Internship interview with MD Mr Siew of inlingua School of Languages on Monday 3 May 2021

I had an opportunity to reach out to my contacts and conduct an interview with Mr Siew, the managing director of inlingua School of Languages to better understand what the organisation does and the programs they offer. Through this, I learnt that inlingua is a 100-year-old language school initially set up in Europe, where there was a need for language education. In Singapore, it was initially tied to a secretarial school but gained independence in 1978. It gained success as more MNCs and foreigners generated new language needs for communication, and there was few international brand schools or schools which offered multiple languages. The organisation’s mission and goals encompass cultural understanding too, in order to provide a more holistic understanding of language.

inlingua offers 21 languages and dialects including Hokkien, Cantonese, and Teochew. The range of needs from its students include healthcare (particularly nurses dealing with the elderly), general/personal use, business and trade for MNCs, government/ministry or statutory boards, students applying to private or international schools, leisure/travel, etc.

The rationale behind the languages inlingua chooses to provide are for personal, business, and government needs. Through government initiatives such as Skills Future, inlingua helps to address government language policies. The significance of learning a second language in a multicultural country like Singapore was demonstrated through the relevance of learning English during the period of economic growth and poverty alleviation. Now, languages serve to maintain the culture and connections which Singapore has to others and within their country.

Singaporean culture places a large emphasis on education, evident in competitive university placements, after-school tuition, and what is jokingly referred to as kiasu culture. An aspect of this emphasis on education is language planning through various government policies. These policies are not without their controversies, such as the “Speak Good English Movement” which aimed to reduce the use of colloquial English (Singlish). With Singapore being a multilingual country, I was curious as to how these policies were enforced, and more broadly, the role of the private sector in supporting government policies.

A notable case is China’s recent ban on private tuition, reason being the inequality created amongst students and unfair opportunity. Similar topics of contention related to the relationship between the government and private institutions is the privatisation of the NHS in the UK. Applied to a Singaporean context, I could analyse the education system as well as the role of private institutions in providing access to education and fostering a certain type of study/work culture. Furthermore, with the influx of not only local but foreign students engaging with private education institutions, I could explore the effects of globalisation on equality and conflict. My political issue therefore could be along the lines of to what extent should the private sector interfere with government policy. This is of significance as there are mixed opinions regarding collaboration between the public sector and the private one. Criticisms include potential government bias, increased profit-incetive (leading to exploitation), and unequal access to opportunities across various communities. However, it is also argued that government partnerships with the private sector increase efficiency and drive the economy. I would be keen to further explore this relationship through the language education sector as education and language play a tremendous role in the success and opportunities of individuals.

Global issue: Beliefs, values, and education

Zoomed in global issue: Different forms of violence which are nurtured and developed in both individuals and societies

How do both texts explore the effects of social structures and culture on the manifestation and/or exacerbation of different forms of violence?

The global issue which I will be exploring is the different forms of violence which are nurtured and developed in both individuals and societies. Violence most often is recognised as a physical behaviour, but other factors like social constraints and power dynamics in various environments often hide subtleties or dilute other forms that violence can take. In ‘Human Acts’, a South-Korean novel based on the 1980 Gwangju pro-democracy uprising, Han Kang explores the effects of state terrorism and repression on all types of civilians, particularly student groups and women, and the ramifications of the event on Korean politics and current society. In the satirical play ‘God of Carnage’ originally set in modern Paris and based around the efforts of two sets of parents intending to resolve a conflict between their children, Yasmina Reza explores the constraints of civilisation, class, and colonial social attitudes in fostering enmity and malice, as well as highlighting the precariousness of intangible conflict of interests and values. Both texts condemn the role of social structures and power dynamics in cultivating or exacerbating the effects of various forms of violence.

Human Acts

The interesting focus on the tension between the government and the people in Kang’s novel ‘Human Acts’ allows for an exploration into the various meanings of nationalism, values and beliefs of Korean society. The polyphonic structure of the novel embodies this tension by featuring individual stories and experiences, weaved together by the common thread of the event of the Gwangju massacre. This structure challenges the state censored, broad sweeping narrative by delving into the complex effects of trauma, sacrifice, relationships, death, and violence on individuals. The non-linearity of events mimics the uncertainty of the process of memory itself and demonstrates the complications of collective memory given the vastly different experiences and perspectives within a single event. This tension of collective and individual memory is explored through the different female characters and the novel’s representation of the female experience. Chapters like ‘The Editor,’ ‘The Factory Girl,’ and ‘The Boy’s Mother’ provide direct insight into each of the characters lives, and indirectly through their relationships and roles in society. In all three cases, Kang demonstrates the bittersweet reality of the female experience constrained by society who remain, yet examples of strong-willed women, who persevere in their different ways through times of adversity. These repressions of freedoms and normalisation of patriarchal behaviour shape the way in which the female characters deal with authority and internalise their subordinate roles. By enduring these pressures of violence, these women helped shape the history and course of Korean politics for generations to come. But while it can be argued that these women are figures of strength and fortitude for various members of Korean society, it is important to consider the sacrifice of their wellbeing, safety, and lives as a result of their exposure to such unwarranted occurrences of violence. This, in the process, raises questions as to what feminism and the female experience means in the context of an Asian, patriarchal, and conservative society.

Given this context, Kang explores the effect of culture and education on perpetuating values around femininity and women’s roles in Korean society. A notable demonstration of this is through the chapter ‘The Factory Girl’ which follows the life of Seong-ju, one of the activists introduced in the first chapter, after the Gwangju Massacre. Seong-ju recalls a specific memory where Seong-hee, the leader of their female labour party instructed “hundreds of young women” to “take off your clothes” and wave their “blouses and skirts in the air, shouting ‘Don’t arrest us!’” This is illustrative of the ways in which the factory girls were conditioned to think that the “naked bodies of virginal girls [were] to be something precious, almost sacred,” and thus “the men would never violate their privacy by laying hands on them now, young girls standing there in their bras and pants.” This imagery of naked bodies of virginal girls draws similar parallels to infants or babies i.e. not only sexualisation of girls but infantilization too. This reveals wider societal attitudes which are demeaning toward women – as perhaps dependent, innocent, immatured, less capable and only valued in society if they possess these subordinate traits with circumscribed freedom and autonomy.

These instructions by Seong-hee emphasise the value of chastity of a female. The stress on the nouns ‘young girls’ or ‘factory girls’ instead of terms such as ‘women’ or ‘adults’ suggest an exploitative aspect of Korean society in sexualising young girls. To an extent, it can be argued that this form of sexual exploitation is so deeply rooted in Korean society that it is internalised by the women themselves, demonstrated by Seong-hee’s instructions to her fellow group of girls. As the labour party leader and thus a symbol of authority, Seong-hee’s instructions demonstrated the manipulation of the youth, in particular the perception of young women. This draws parallels to the novel’s larger themes around youth movements and the motif of the boy, Dong-ho, and the unintended and collateral sacrifice of the youth and their vulnerabilities to such violence due to their limited experience and naivety. On the other hand, Seong-hee’s instructions could be seen as a deliberate and supposedly necessary measure to ensure these factory girls their survival under these external circumstances. Given the external constraints, Seong-hee hoped to use nakedness to their advantage or to ensure their survival, which could be a demonstration of her astuteness and rational action under dire circumstances. Unfortunately, the factory girls’ only action to stop the soldiers can be seen as a last desperate measure, limited of any choice and subjected to a violent ending.

Despite their efforts, the factory girls were still abused and captured as “the men dragged them down to the dirt floor.” The harsh physical abuse and humiliation tell us about the girls’ misconceived idea and the illusion of societal values in the protection of young women. The description of “gravel scraped bare flesh, drawing blood” and “hair became tangled, underwear torn” emphasises the girls’ nudity and bareness, heightening the image of this physical violence. This jarring image is also constructed through the juxtaposition of words such as ‘bare’, ‘flesh’, ‘hair’ and ‘gravel’, ‘tangled’, ‘torn,’ phonically producing fricative and interdental sounds and creating a contrasting image of something delicate and light ruined by something abrasive or sharp. This imagery of bareness could also be symbolic of women being particularly vulnerable to different forms of violence in a violent patriarchal society. Kang further emphasises this by the description of their “ear-splitting cries” and “the sound of square cudgels slamming into unprotected bodies, of men bundling girls into riot vans.” The use of weaponry on ‘unprotected bodies’ and the physical difference in strength between ‘men’ and ‘girls’ displays the intentional and unnecessary violence which was deliberately committed, despite the clear demonstration of the factory girls’ defencelessness.

Altogether, it can be seen that the existence of these societal values and norms which subject women to exploitation and violence are deep-rooted in the social structures of patriarchy. The internalisation of these values in part help perpetuate them and allow for the cultivation of other forms of violence, such as physical abuse. Kang explores the female experience through the context of a more vulnerable group of society simultaneously dealing with oppressive and demanding expectations and roles as women, and other acts of violence like state terrorism. Nevertheless, Kang portrays these women in a dignified manner by showing their commitment and unity in both the protesting and suffering endured.

God of Carnage

In Reza’s play ‘God of Carnage’ we can see parallels to ‘Human Acts’ in the manifestations of indirect forms of violence and social structures. In terms of social structures, the context is set in modern Paris, and therefore allows Reza to explore themes related to Western society like civilisation and colonialism. Education and social interaction are most predominantly explored through each of the couples’ parenting, revealing their personal values and beliefs toward conflict resolution. As the play is narrated and mediated by the parents, tension can be observed between protecting family interests and upholding personal or societal values. This is most evidently shown through Michel’s wife, Veronique, who is characterised by her efforts for a civilised resolution and attempt to claim the moral high ground. Yet her ultimate resort to physical violence, convenient shift in allegiances, and condescending attitudes toward other cultures demonstrate the fragility of peace and quick degeneration into violence. The irony of Veronique’s verbal and physical acts of violence could be a wider critique of the Parisian elitist society she represents. Reza initially constructs her elitist character through the way in which Veronique interacts with other characters, by her fixation with political correctness, as well as the way in which she views and carries herself, her self introduction as a specialist in ‘Africa’ and contribution to “a collection on the civilisation of Sheba” “and a book coming out on the Darfur tragedy.” As the setting takes place in the Vallons household, the furniture and decor also serve to reinforce Veronique’s character. For instance, the coffee table decor such as the jar of tulips is supposedly symbolic of aesthetic beauty, or the coffee table art books, which are symbolic of wealth and knowledge and often used to identify the upper class. Both her crafted image and decor are pretensions to high culture and comically the conflict and unfolding of events were to later destroy.

As the play develops, there are heightened points of tension whereby Veronique becomes increasingly passive-aggressive, revealing more of the contradictions between her beliefs and actions. A notable demonstration of this is toward the end of the play, at this point where all the characters have abandoned their courtesy and civility. This instance was most damaging to Veronique’s image, who tried hard to establish “she’s a supporter of peace and stability in the world.” At a simple remark, she physically assaults Michel, where she “throws herself at her husband and hits him several times, with an uncontrolled and irrational desperation.” The irony is that the whole play revolves around her desperation for a resolution to the violent conflict between the children, to which she herself has finally succumbed. The description of her ‘uncontrolled and irrational desperation’ could symbolise an outburst of suppressed emotion and violence, and thus serves to reinforce Alain’s belief in “the god carnage” which has “ruled, interruptedly, since the dawn of time.” However, once more, Veronique proceeds to claim “we’re living in France” and “not Kinshasa,” and therefore “living in France according to the principles of Western society.” The reference to Kinshasa serves to elevate the civilised status of France and imply that Kinshasa is less civilized and ought to aspire to a higher level of civility which only Western society has achieved. It can therefore be argued that her beliefs of civilisation and peace are inherently condescending.

Reza portrays that Veronique’s violent attitudes are not necessarily stemming entirely from ignorance, but perhaps values comparable to a colonialist mentality. Part of this is shown from her boast in her ‘expertise’ in Africa, to which she asserts “don’t lecture me about Africa” “I’ve been steeped in it for months…” Ironically, such overgeneralization could convey her condescension or a false sense of erudition. This ‘expertise’ becomes particularly dangerous, as she appears to make claims or impose values related to civilization from a sense of higher morality that draws parallels to colonists’ attitudes. In addition, she suggests that everyone adhere to such values when she states “what goes on in Aspirant Dunant Gardens reflects the values of Western society,” and her proud acknowledgement “of which, if it’s all the same to you, I am happy to be a member” adds to that perception. It is well known of the adverse impacts from colonialism, both the structural and physical violence on societies.

The play ultimately ends in a cycle of conflict, each degenerating into worse verbal and physical damage, the pattern of violence that the adults fail to escape. Reza emphasises how Veronique’s mentality can lead to intolerance and superiority, fueling their argument. The irony of Veronique’s actions and the triviality of her behaviour ridicules the colonial mentality and elitist stereotype she represents.

In both bodies of work, we can observe a perpetuation of different forms of violence and an inability to find a resolution and closure. In ‘Human Acts,’ the societal pressures of a patriarchal society and its effect on the role of women can be seen as a form of structural violence. The legacy of the Gwangju massacre remains traumatic and unclosed for many victims due to the lack of accountability of authority. Part of the perpetuation of the violence is the lack of transparency and discourse around the wrongdoings of the Korean government and injustices to the population. Here, education can play a role in giving meaning to the victims’ sacrifices and informing future generations of what biases have shaped the historical period. In comparison, the violence demonstrated in ‘God of Carnage’ may appear to be satirized, yet remain important lessons in a world where bigotry and ‘cancel culture’ continue to create division within present society. Interestingly, this is where education does not necessarily bridge the differences in values and beliefs to prevent violence. The existence of differences between our values and beliefs may result in conflict. ‘Human Acts’ tells us, on a political level, the atrocities and cruelties which human beings can commit. The satire of ‘God of Carnage’ demonstrates how humans, on a personal level, under a ‘civilised’ society, can easily veer into violence, if there are no shared values or compromise. Peaceful coexistence requires much effort and cannot be taken for granted.