Essay

Extract: page 135-6, from the story “Speaking of Courage”.

And then he would have talked about the medal he did not win and why he did not win it.

“I almost won the Silver Star,” he would have said.

“How’s that?”

“Just a story.”

“So tell me,” his father would have said.

Slowly then, circling the lake, Norman Bowker would have started by describing the Song Tra Bong. “A river,” he would’ve said, “this slow flat muddy river.” He would’ve explained how during the dry season it was exactly like any other river, nothing special, but how in October the monsoons began and the whole situation changed. For a solid week the rains never stopped, not once, and so after a few days the Song Tra Bong overflowed its banks and the land turned into a deep, thick muck for a quarter mile on either side. Just muck—no other word for it. Like quicksand, almost, except the stink was incredible. “You couldn’t even sleep,” he’d tell his father. “At night you’d find a high spot, and you’d doze off, but then later you’d wake up because you’d be buried in all that slime. You’d just sink in. You’d feel it ooze up over your body and sort of suck you down. And the whole time there was that constant rain. I mean, it never stopped, not ever.”

“Sounds pretty wet,” his father would’ve said, pausing briefly. “So what happened?”

“You really want to hear this?”

“Hey, I’m your father.”

Norman Bowker smiled. He looked out across the lake and imagined the feel of his tongue against the truth. “Well, this one time, this one night out by the river… I wasn’t very brave.”

“You have seven medals.”

“Sure.”

“Seven. Count ‘em. You weren’t a coward either.”

“Well, maybe not. But I had the chance and I blew it. The stink, that’s what got to me. I couldn’t take that god-damn awful smell.”

“If you don’t want to say more—”

“I do want to.”

“All right then. Slow and sweet, take your time.”

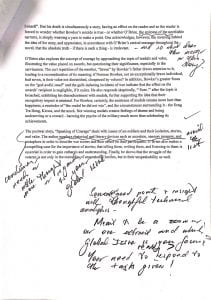

Analytical Essay

The collection of short stories “The Things They Carried”, written by Tim O’Brien, is a metafictional novel which recounts a series of episodes from the Vietnam War, based on the author’s personal experiences. In the story, “Speaking of Courage”, which tells the tale of Norman Bowker, a former soldier now returned to his home in Iowa. Unable to find emotional release in the sharing of his experiences, he feels maladroit in his once-familiar hometown as he sees the figures of his childhood have moved on. In this extract, the titular theme of courage as well as those of community and identity are discussed as O’Brien illustrates the difficulty of post-war life for servicemen and the catharsis that comes from stories, even those that are imaginary.

O’Brien examines the struggle of war survivors through sensory language, and accretion. He first outlines the force of the initial event, using intense olfactory and tactile imagery to describe the environment of the Song Tra Bong river; how “You’d just sink in.” and “feel it ooze up over your body”. The combination of polysyndetic compound sentences with the repetition of the personal address “you’d” in dialogue and the powerful connotations of words such as “ooze”, “suck”, and “muck” align to create a vivid picture. The use of short, common words, often monosyllabic (90% of the first sentence’s words containe one syllable), contributes to the strength of experience portrayed as the reader wades through sentences which themselves feel thick and dense . The Song Tra Bong river, in a way, is in fact a metaphor for the war itself; unending and muddy with people attracted by the figurative pull of duty. The weightiness of sentiment and of emotional state is supported by the accretion employed as Bowker drives rounds around the lake; with each lap, details are updated and added, slowly building up the heaviness on his mind through narrative layering.

O’Brien then conveys the gap between Norman Bowker and his fellow citizens, thus elucidating the continuing suffering of ex-soldiers. That the conversation between Bowker and his father is entirely imaginary underscores the idea that Bowker is no longer able to feel at home. The use of continuous conditional language with “would” serves as a constant reminder that Bowker has no-one to actually talk to; the audience is witnessing his internal thinking, rather than literal dialogue. Despite his longing to talk about his memories, evidenced when he “imagines the feel of his tongue on the truth”, the metaphorical language implying his desire to converse openly, he does not have the opportunity to do so. He wishes for a father that will say, “‘So tell me, then’”, and ask for his stories – “‘I’m your father.’” – but does not have one. Elsewhere in the story it is mentioned that he lives in a “brisk, polite town”, which “did not know shit about shit” (the expletives here enforce the meaning and represent the understanding coming from war). He no longer understands the town people, and the town people no longer understand him. As such, he does not belong; with Sally Kramer now Sally Gustafson (the repetition of this fact through the layers lends it importance, the name change being indicative of a larger one) and Max dead, with no-one to talk to, there is little solace in the place he once called home. The effects of war continue to resound in former army men’s lives, as they are disconnected from their communities, their identities shaped irreversibly by the events witnessed.

The power of storytelling is also touched on here, as O’Brien, through metafiction, treads the line between truth and story-truth. In the following, closely related story, “Notes”, it is revealed that (supposedly) this particular part of the story – the loss of the Silver Star – comes from Tim O’Brien; that is, it happened to him, rather than Norman Bowker. In retrospect, the line, “‘Just a story’.” is ironic and displays foreshadowing as the tale recounted is nothing more; a story, not his story. Upon learning further of Bowker’s suicide, abruptly mentioned in the simple sentence, “Eight months later, he hanged himself.”, the audience is jarringly made to realise the vital importance of telling stories, and what can result when one leaves them unsaid. This is elaborated on throughout the book as O’Brien makes personal references to the redemptive quality of writing, saying that he wrote to “save himself”. But his death is simultaneously a story, having an effect on the reader and so the reader is forced to wonder whether Bowker’s suicide is true – or whether O’Brien, the epitome of the unreliable narrator, is simply weaving a yarn to make a point. One acknowledges, however, the meaning behind the idea of the story, and appreciates, in accordance with O’Brien’s central message throughout the novel, that the absolute truth – if there is such a thing – is irrelevant.

O’Brien also explores the concept of courage by approaching the topic of medals and valor, illustrating the value placed on awards, but questioning their significance, especially to the servicemen. The curt repetition of the number, “Seven” by Bowker’s father draws attention to it, leading to a reconsideration of its meaning; if Norman Bowker, not an exceptionally brave individual, had seven, is their value not diminished, cheapened by volume? In addition, Bowker’s greater focus on the “god-awful smell” and the guilt-inducing incidents of war indicate that the effect on the awards’ recipient is negligible, if it exists. He also responds skeptically, “‘Sure.’” after the topic is broached, exhibiting his disenchantment with medals, further supporting the idea that their recognitory impact is minimal. For Bowker, certainly, the existence of medals creates more hurt than happiness, a reminder of “the medal he did not win”, and the circumstances surrounding it – the Song Tra Bong, Kiowa, and the muck. Not winning medals creates feelings of shame and being undeserving or a coward – harming the psyche of the military much more than celebrating its achievements.

The postwar story, “Speaking of Courage” deals with issues of ex-soldiers and their isolation, stories, and valor. The author employs rhetorical and literary devices such as accretion, sensory imagery, and metaphors in order to describe war scenes and their effect on their participants. O’Brien also makes a compelling case for the importance of stories; that telling them, writing them, and listening to them is essential in order to gain catharsis and understanding. Finally, he shows that the struggle of the veteran is not only in the memories of unspeakable horrors, but in their unspeakability as well.